by Crystal Caudill | May 25, 2017 | History Facts

This week I am wrapping up my Secret Service series with a look at the other side, counterfeiting in the late 1800’s. While there is a lot more information to share, I just broke the counterfeiting scheme down to five basic steps with tidbits of extra information. Enjoy, and don’t get into too much trouble!

For unfamiliar terms, please visit last week’s post: Secret Service Dictionary and Fun Facts

The Process of a Counterfeiting Scheme:

Step One: Engrave plates for use on printing presses.

- Engravers were particularly scarce; those who did succumb to thievery had to serve many masters and lived rather hectic lives.

- Engravers earned between twenty to forty dollars a week and worked nearly a year to finish a set of plates.

- There was a market for used plates. A good set of plates could be sold for between several hundred and two thousand dollars.

Step Two: Print the Money

- Like the manufacturers of legal merchandise, criminals needed to consider opportunity, risk, demand, price, and quality before investing their capital, time, skills, and organizational talent in the business.

- The effort, time, and money (several thousand dollars) needed to produce an issue put the manufacturing of counterfeit notes beyond the resources of a single individual.

- Plates belonged to one partner – either because he had provided the money to have them made or because he took them as part of his share in the proceedings.

- Manufacturers used areas where there were a large number of supply stores clustered in the area to sell paper, type, ink, and various kinds of presses, which

were the raw materials of counterfeiting.

were the raw materials of counterfeiting.

- Knowledge and techniques were transmitted orally and perfected by practical experience in saloons. Counterfeiter’s reliance on an oral culture and on personal relationships effectively shielded them from the police.

- A firm could print between ten thousand and twelve thousand dollars a month.

Step Three: Sell to a Wholesaler

- The wholesaler was the key figure in the distribution process. If the wholesaler was a member of the production firm, he had direct access to the product without any additional costs beyond his original investments in the partnership.

- The whole seller sold product to dealers/retailers.

Step Four: Sell to a Dealer/Retailer

- There were two types of dealers: (1) Thieves who bought counterfeits to pass on unsuspecting merchants or (2) Merchants who were willing to cheat their customers by giving them counterfeit money in change.

- Dealers created customer lists, which they jealously guarded from their competitors. Their customers regularly wrote to the retailers or left messages at the saloons that retailers visited.

Step Five: Shove the Money – (A.K.A. Put counterfeit notes into circulation.)

- Shovers usually operated in small groups of two or three. One shover entered a

shop, made a small purchase, and received genuine money in change. While the shover was transacting business, a companion remained outside to watch for the police and to make sure that the shover was not followed by the store keeper, who might have discovered the counterfeit.

shop, made a small purchase, and received genuine money in change. While the shover was transacting business, a companion remained outside to watch for the police and to make sure that the shover was not followed by the store keeper, who might have discovered the counterfeit.

- After each transaction, they placed the proceeds in a separate pocket or envelope, so that their associates would be able to trace the precise amounts each shover collected.

- Then the group returned to their meeting place and divided the proceeds.

The Price of Counterfeiting:

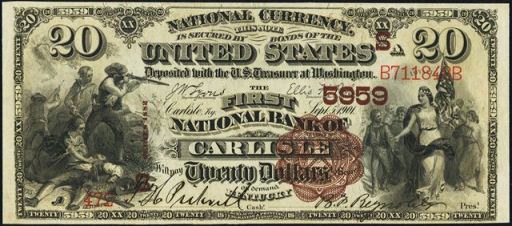

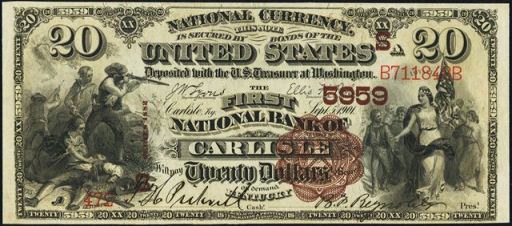

The price of counterfeit bills fluctuated based on their quality and lack of public awareness. New notes were easy to pass and thus sold for more money, generally between thirty and seventy cents. The better the counterfeit quality, the better the price.

As soon as a new counterfeit’s existence became widely known, dealers had to lower the prices to compensate their customers for the increased risk. Discounted notes sold for between eighteen and twenty-two cents on the dollar.

by Crystal Caudill | Apr 27, 2017 | Counterfeit Love, History Facts

Just as any career has its own jargon, so did the counterfeiting world and the Secret Service. Below are a few of the most important terms to know. Below that are a few fun facts about the Secret Service.

Secret Service and Counterfeiting Dictionary

- Boodle – notes bought from a production firmBoodle carrier – a courier who delivered counterfeit notes from the dealer to the shovers.

Chief Operative – first-class men assigned to the division’s major districts, each chief operative would have assistant operatives working under his direction, and would be responsible for all administrative and investigative activities within his district.

Dealers – people who bought the counterfeit notes from wholesalers and then used shovers to distribute the money into general circulation

Distribution – the spread of counterfeit money through an underground sales network

Engraver – the person who created the plates used to print money

Firm – the collective group of people used to print money

Issue – an edition of a set of counterfeit bills

Manufacturer – a person or group of people who printed counterfeit money

Network – the sum of one’s personal acquaintances (which included non-criminals).

Notes – another term for paper money

Operative – the official title of the Service’s employees

Plant – a term used to reference where counterfeiters made their money

Plates – metal pieces with copied images from the bill being counterfeited

Product – another name used for counterfeit money, generally used by the counterfeiters

Production Firm – the collective group of people used to print money

Queer – another term for counterfeit money

Retailer – another term for a dealer

Shover – a person who bought low priced items with a higher counterfeit bill to get real money back in change

Straw bail – a situation in which a false bondsman was contracted to swear they possessed sufficient property to pay the bond, and then the counterfeiter would subsequently fail to appear in court

Wholesalers – men or women who would buy counterfeit notes from manufacturers and then recruit potential customers through personal contacts or the mail to create a sales network

-

Fun Facts about the Secret Service

- D.C. was the Service’s bureaucratic headquarters and the chief lived there

- Between 1875 and 1910, the division never employed more than 47 men, and the average was only 25. 1878-1893, the average number of servicemen was well below that.

- Chief operatives often had several cases under investigation at once and had

testy battles with headquarters over conflicting demands for economy and results

testy battles with headquarters over conflicting demands for economy and results

- Each chief operative maintained a retinue of assistants and informers

- Each district contained a number of states and a single operative maintained a headquarter in a major city

- There were field offices in 11 cities across the nation.

- Operatives were paid once a month on a daily scale, an average of $7 per day.

- Each work day ranged from 12 to 16 hours long.

- There were no days off and any “vacation” time was unpaid.

- Operatives were required to itemize all their expenses for everything from travel to personal needs.

- Operatives were to maintain peak physical fitness, swear unquestioning obedience to chief’s directives

- In 1881, all toy money was removed from shelves and industries.

- While time-consuming, the work was not particularly dangerous (no Service employee was seriously hurt in the line of duty until the murder of an operative in 1908).

by Crystal Caudill | May 5, 2016 | Counterfeit Love, History Facts

“The detection of crime, when entered upon with an honest purpose to discover the haunts of criminals and protect society from their depredations by bringing them to justice, is held to be an honorable calling and worthy of commendation of all good men.”

– Hiram C. Whitley, Chief of the Secret Service, May 1869 – September 1874

While many people today think of the Secret Service as primarily protecting the President, that duty did not actually become a part of their repertoire until 1894. Until 1902 it was conducted only informally and part-time, and even then, only two operatives were assigned full-time to the White House. So what did they do from their creation in 1865 until 1902, and beyond?

Before the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) was given exclusive authorization of currency production in 1877, our our government was in a precarious situation. Prior to the formation of said currency, one third to one half of all money in circulation was counterfeit. Determined to ensure the safety of the new national currency, the Secret Service was tasked with detecting and bringing to justice the counterfeiters whom were so talented at creating the illegal tender.

Enter the heroes of my series in progress. Each hero is a Secret Service operative from the early days when detecting counterfeiters was their man job and concern. My current hero is working a case in 1883. Researching the cases of these amazing heroes has been a revealing and enjoyable adventure.

More posts will be devoted to these amazing heroes of our early economic system, but for now here are few interesting facts gleaned from my research of the Secret Service prior to 1901:

- The number of operatives in the Secret Service ranged between fifteen men in 1865 and a high of thirty-five in 1898 for the entire United States. A large portion of that time the number of operatives was well below thirty.

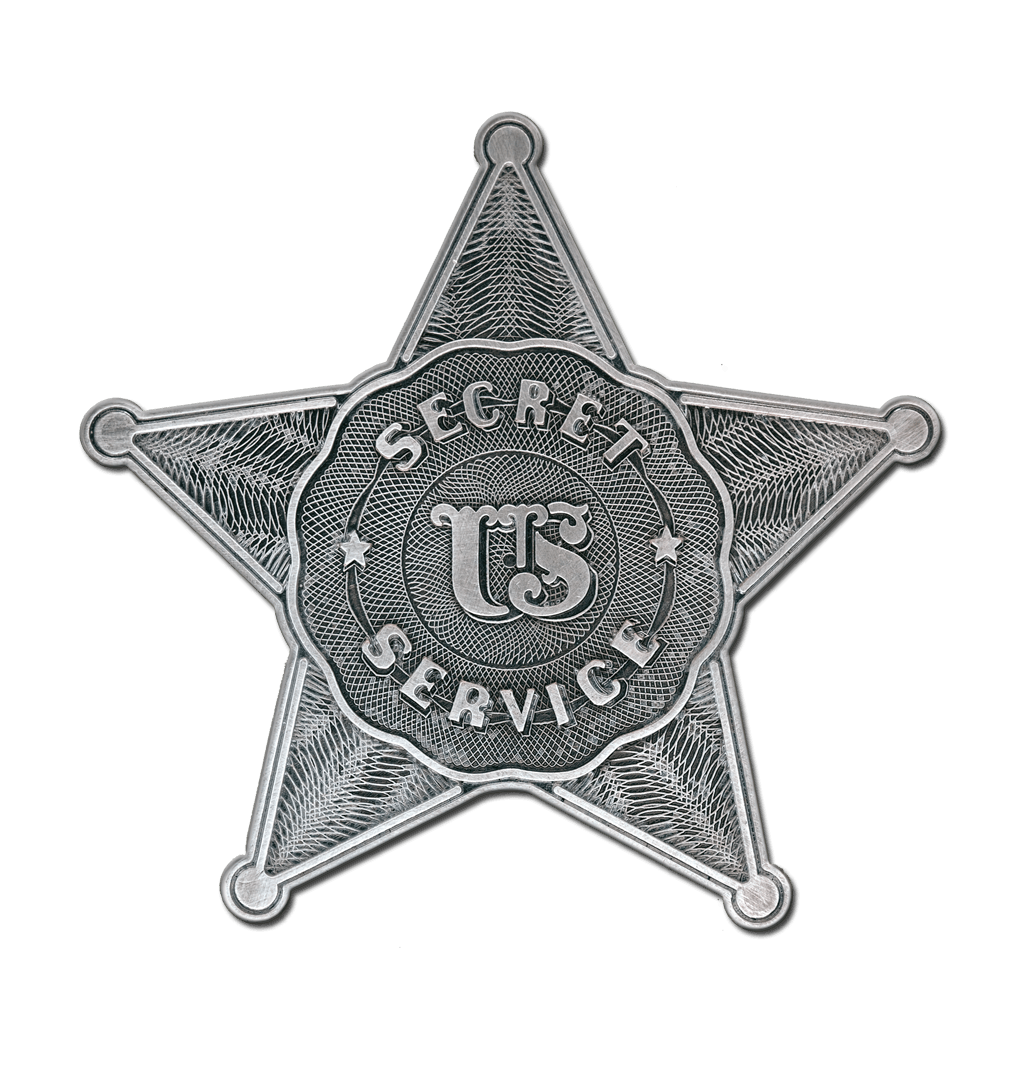

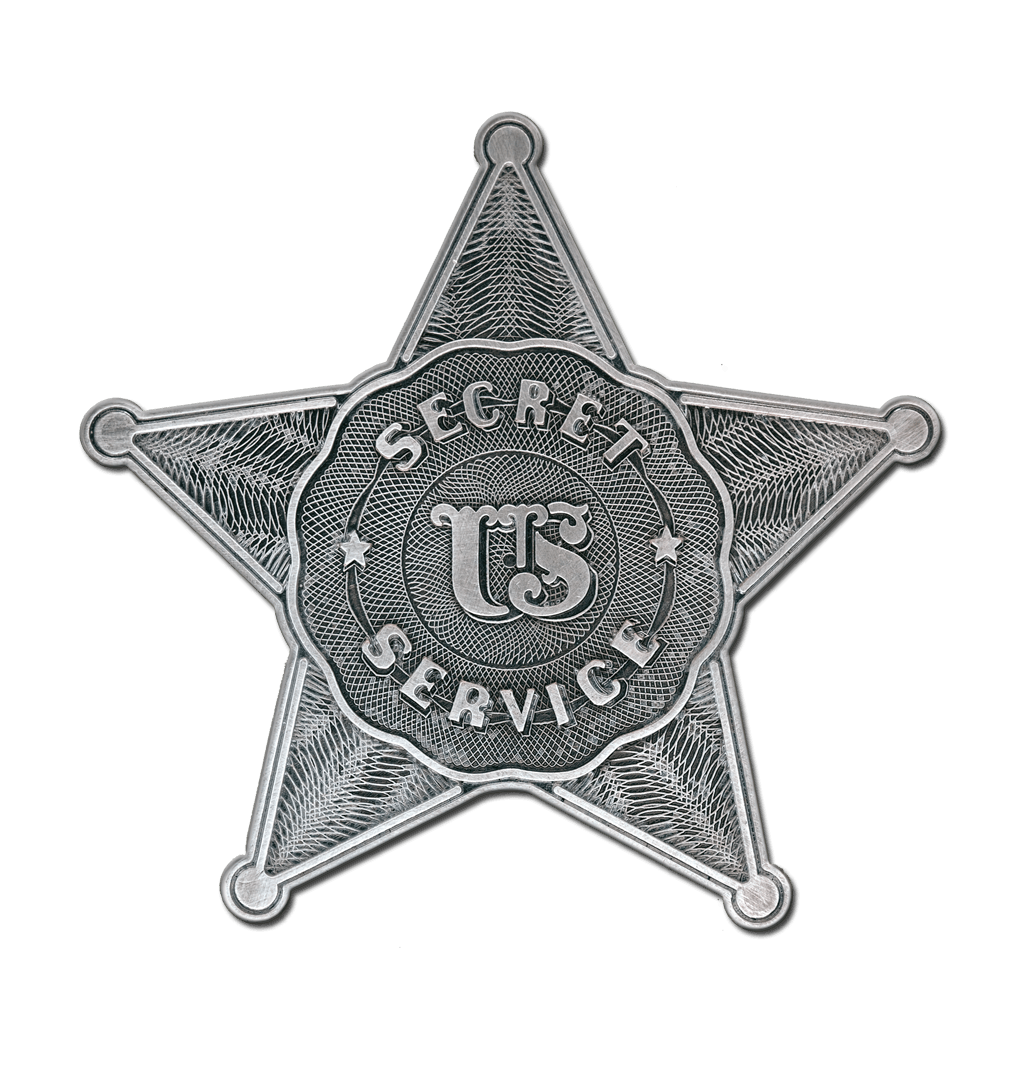

- The badge below was issued in 1875 and was the first to feature the “Service Star” – the official emblem still used today.

- The star’s five points each represent one of the agency’s five core values: justice, duty, courage, honesty, and loyalty.

- Secret Service operatives not only located and shut down counterfeiters, they also investigated nonconforming distillers, smugglers, mail robbers, land frauds, and other infractions against the Federal government.

- Secret Service operatives were not initially allowed to arrest criminals, therefore they had to work in conjunction with local police.

- U.S. Marshall’s once earned extra income through the reward money granted for the capture of counterfeiters. When the Secret Service took over that duty, tension developed between the two agencies. Eventually this faded, but in those early days working together was not always done amicably.

were the raw materials of counterfeiting.

were the raw materials of counterfeiting. shop, made a small purchase, and received genuine money in change. While the shover was transacting business, a companion remained outside to watch for the police and to make sure that the shover was not followed by the store keeper, who might have discovered the counterfeit.

shop, made a small purchase, and received genuine money in change. While the shover was transacting business, a companion remained outside to watch for the police and to make sure that the shover was not followed by the store keeper, who might have discovered the counterfeit.

testy battles with headquarters over conflicting demands for economy and results

testy battles with headquarters over conflicting demands for economy and results